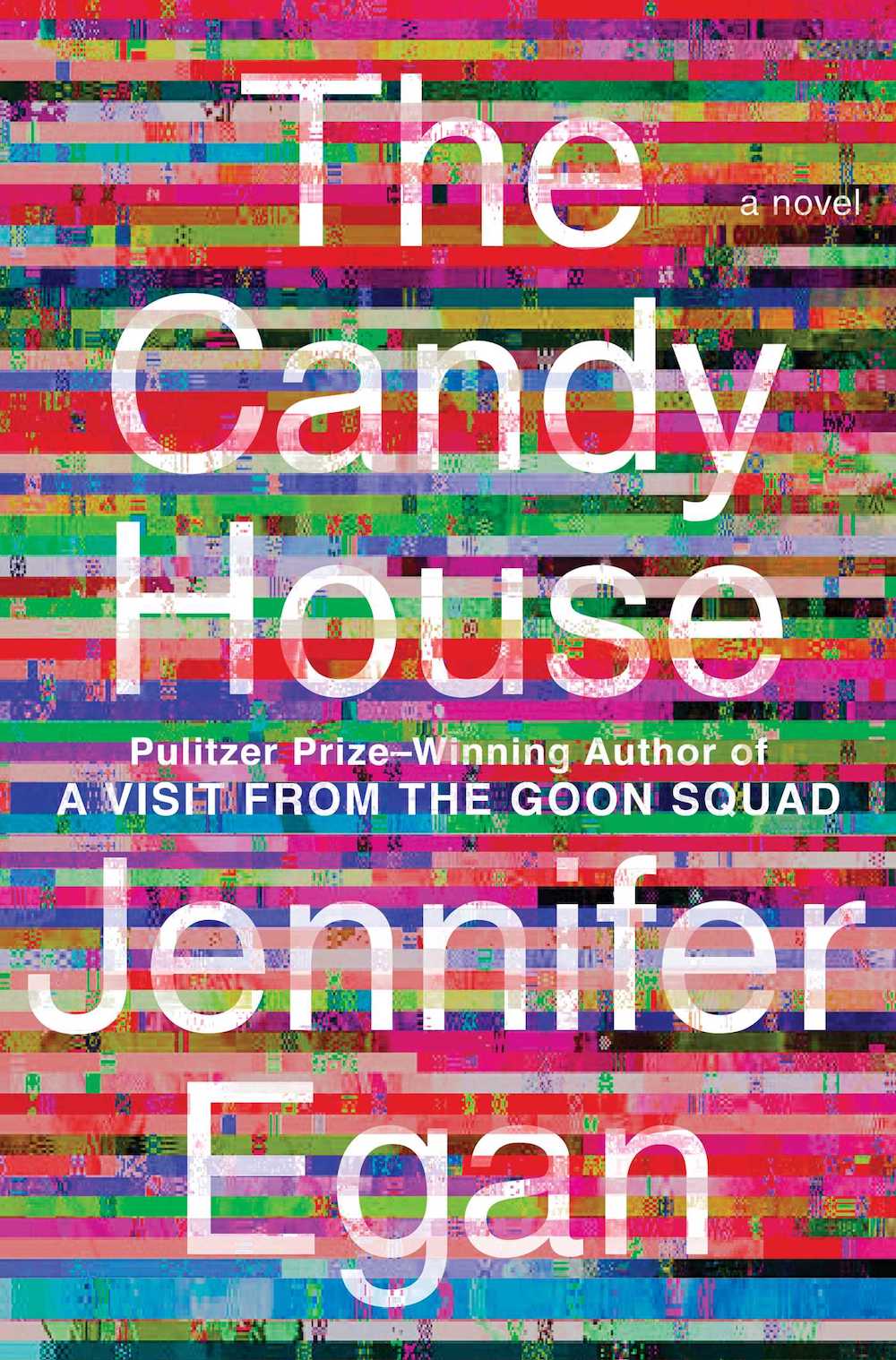

The Candy House

Jennifer Egan

I understood with sudden clarity that doing the right thing — being right — gets you nothing in this world. It’s the sinners everyone loves: the flailers, the scramblers, the bumblers. There was nothing sexy about getting it right the first time. Fuck Sasha, I thought. I'm fully aware that Sasha emerges from these descriptions as sympathetic, whereas I come off as a moralizing prig. I was a moralizing prig, and not just toward my cousin. My father, who treated Sasha as a daughter and whom I saw as her enabler; my mother, whose romantic adventures since my parents' divorce I found sickening; my younger brothers, Ames and Alfred, both of whom I'd deemed "lost" before they turned twenty-five — no one escaped the roving, lacerating beam of my judgment. I can access that beam even now, decades later: a font of outraged impatience with other people's flaws. How had the human species managed to survive for millennia? How had we built civilizations and invented antibiotics when practically no one, other than Trudy and me, seemed capable of sucking it up and just getting things done?

But I hadn’t counted on the circularity of life: the way it delivers us, with age, back to the beginning.

Mysteries that are destroyed by measurement were never truly mysterious; only our ignorance made them seem so.

Knowledge is power, so they say, and yet any counter will tell you that merely possessing data, in itself, is neither useful nor predictive. Does it help me to know that, in the roughly 5.224 months they have been dating, M and Marc have spent the night approximately one out of three, or 53.07, nights?

The random walk of a drunk is of geometric interest, but it can’t predict where he’ll stagger next.

A bright moon can astonish, no matter how many times you have seen it.

But knowing everything is too much like knowing nothing; without a story, it’s all just information.