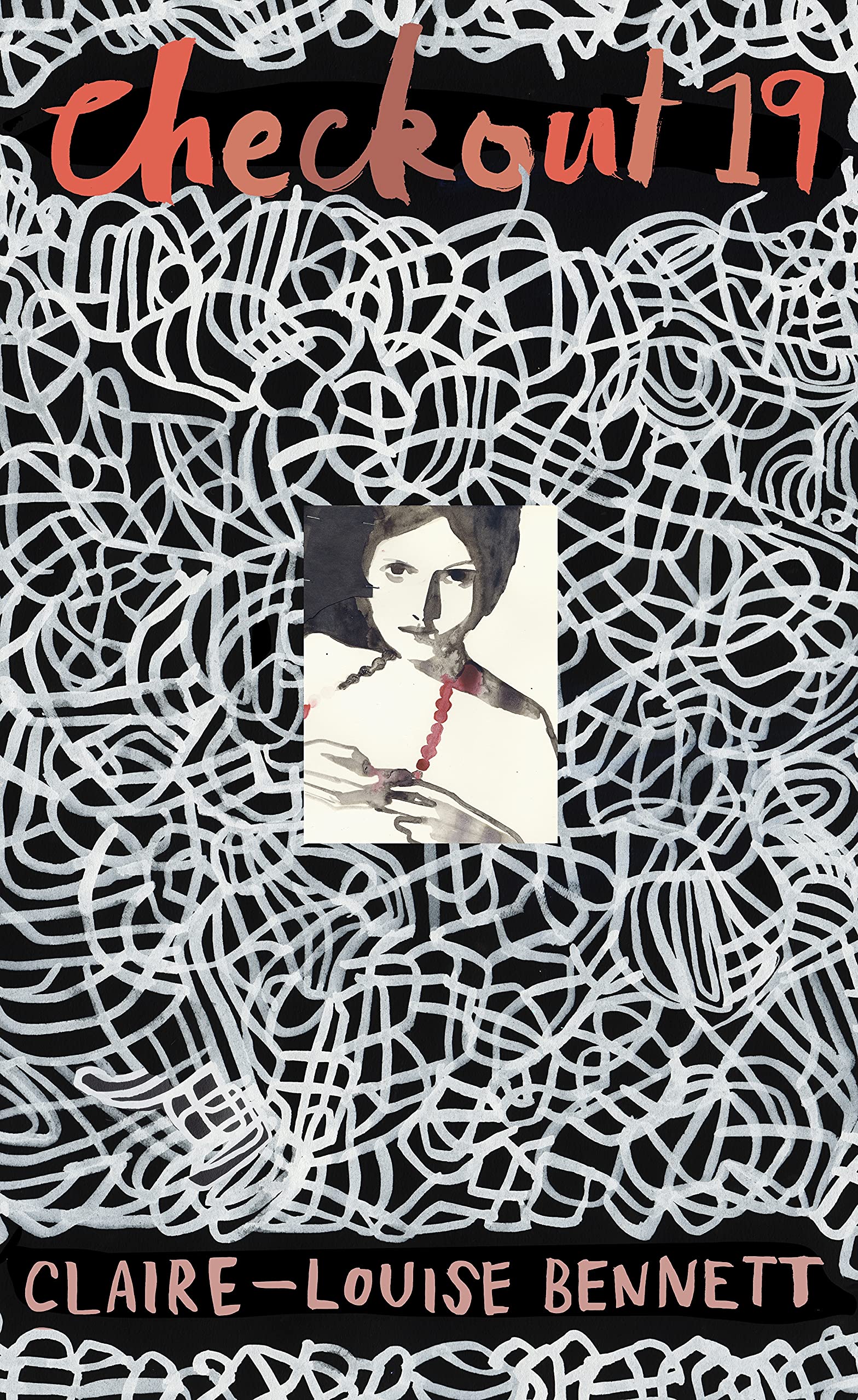

Checkout 19

Claire-Louise Bennett

On and on I experienced gapin periods of time when I was flattened by a sense of doom.

Sometimes I think of asking for it back. But I can't bring myself: 'Can I have my book back please?' No, I am just quite unable to say that. I can buy it again of course, and one day that's what I'll do I expect. And as I go along reading it again I'll underline sentences here and there once more, but they won't be the same sentences — it's very likely that the sentences I'll underline in future will be different from the sentences I underlined in the past, when I was in Tangier - you don't ever step into the same book twice after all.

You don't believe in shelves, do you?

Poetry rips right through you, makes shit of you, and a man can be made shit of and go on living because no one really minds, not even the man. The man likes it in fact, likes to be made shit of so that he can sit there and drink his head off and declaim one epithetical thing after another and all the other interminably taciturn men believe he is an exceptional man, a man taking a hit for them all, a hero really, a ramshackle hero they'd love to raise up upon their shot-to-fuck shoulders of else roll about in the muck with, for wasn't he a down-to-earth sort of a fellow after all? But it's dreadful to see a woman who's been made shit of.

Many of the books I read by women were written when this or that woman was sad or was reflecting upon a time when she had felt sad and when I say sad I'm being coy of course, but what else can I say? Adrift? At odds? Displaced? Out of sorts? Out of her mind? At her witsend? From another planet? Anna Kavan, for example, she doesn't want the day, she's not interested in all of that, because for one thing she went to school during the day and that wasn't where she belonged, there's too much reality in the day for another thing, everything is visible, on and on, for miles in every direction, and hardly any of it is especially engaging.

One is relentlessly overwhelmed and understimulated all at the same time.

I probably went back to my B&B and on up the stairs all cosy and lay on the bed with a cigarette after all that disgruntlement with Billy. And that was all there was to it me on the bed no texting no emailing no one knew where I was it wasn't as if I told my parents or my housemates, perhaps I'd told Dale. Probably I had but quite often people didn't know where you were what you were doing nor how you felt about it either. You just had to lie there oftentimes, that was all there was to it. And I loved that feeling of no one knowing. And went on loving it. Treasuring it. I treasured it really. Privacy. Secrets. But it became more and more difficult to get that not-knowing and the deeply glamorous feeling that came with it and now it doesn't exist at all the outcast minutes of the day gently claw at you, over here, over here, and it's harder to know where you are or what you're doing and how you really feel about any of it. One's on tenterhooks nearly all the time and there's nothing remotely glamorous about tenterhooks.

Well, it varies from day to day. Sometimes I'm just waiting for a telephone call or the next meal, or to pick my children up, but when I think about it and pose the question to myself I imagine that in time I would've become a different person and the world around me will be different too. There is this constant desire to break out of one's own skin and into another reality. Sometimes you see paintings of rocks or ocean, or wilderness, and you think not only will I go there but I will partake of a whole new kind of experience. I will be born again through those rocks or in that ocean and the I who now suffers and laughs will do it in a different and possibly richer way.