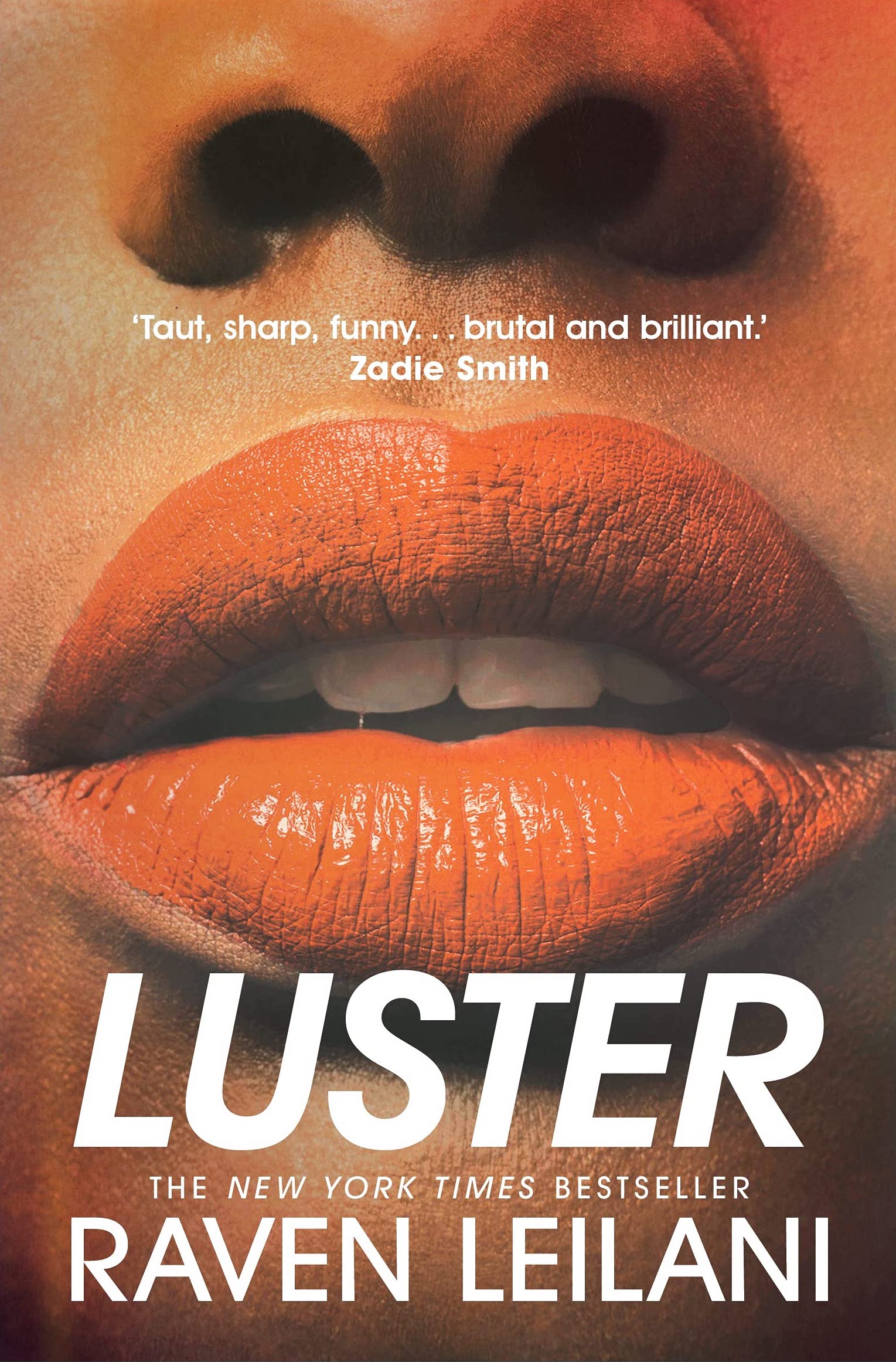

Luster

Raven Leliani

A month is too long to talk online. In the time we have been talking, my imagination has run wild. Based on his liberal use of the semicolon, I just assumed this date would go well. But everything is different IRL. For one thing, I am not as quick on my feet. There is no time to consider my words or to craft a clever response in iOS Notes. There is also the fact of body heath. The inarticulable parts of being close to a man, the sweet, feral thing underneath their cologne, the way it sometimes feels as if there are no whites to their eyes. A man's profound, adrenal, craziness, the tenuousness of his restraint. I feel it on me and inside me, like I am being possessed. When we talked online, we both did some work to fill in the blanks. We filled them in optimistically, with the kind of yearning that brightens and distorts. We had elaborate, hypothetical dinners and we talked about the doctor's appointments we were afraid to make. Now there are no blanks, and when he rubs sunblock on my back, it is both too little and too much.

He frowns, and I realize I have seen this one before, that after a few hours his facial expressions are already becoming familiar to me. When I think of how we will only move forward from here, how we will never return to the relative anonymity of the internet, I want to fold myself into a ball. I hate the idea that I have repeated an action, that he has looked at me, discerned a pattern, and silently decided whether it is something he can bear to see again.

When it's almost 5:00 am, I have a passable replication of Eric's face. The slope of his nose in the soft red light of the dash. I rinse my brushes and watch dawn come in its smoky metropolitan form. Somewhere in Essex County, Eric is in bed with his wife. It's not that I want exactly this, to have a husband or home security system that, for the length of our marriage, never goes off. It's that there are gray, anonymous hours like this. Hours when I am desperate, when I am ravenous, when I know how a star becomes a void.

My roommate and I have been supporting a family of mice for six months. We have gone through a series of traps and yelled at each other in Home Depot about what consistutes a humane death. My roommate wanted to bomb the place.

Because there are men who are an answer to a biological imperative, whom I chew and shallow, and there are men I hold in my mouth until they dissolve.

I have come to the part of the night where I am incapable of any uppercase emotion, and every circuit responsible for my cellular regeneration has begun to smoke.

I think of my parents, not because I miss them, but because sometimes you see a black person above the age of fifty walking down the street, and you just know that they have seen some shit. You know that they are masters of the double consciousness, of the discreet management of fury under the tight surveillance and casual violence of the outside world. You know that they said thank you as they bled, and that despite the roaches and the instant oatmeal and the bruise on your face, you are still luckier than they have ever been, such that losing a bottom-tier job in publishing is not only ridiculous but offensive.

By the time I feel able to contribute to our conversation, it becomes obvious that it is not a conversation. It becomes obvious that he does not intend to acknowledge punching me in the face or the terrible, revelatory night I spent at his home. The texts come intermittently and without any prompting, though Eric usually sends them at around noon and midnight, which tells me that I occur to him during lunch and perhaps while he is still in bed. In between these texts, I want to ask him what he's eating. I want to ask him why he is awake. But then I worry he'll remember I'm on the other end and the texts will stop. This is the way it was when our relationship only existed online. We told each other things so awful that by necessity we adopted the posture of speaking in jest, though we had gone through the trouble to create a language, and the effort of this alone betrayed our seriousness. And then we met.

My reliance on the city's density, which I have spent so much time hating but proves to be the last barrier between me and some inconceivable bosslevel of concentrated loneliness.

"Imagine living life so carefully that there are no signs you lived at all," she says. "I thought I was going to be a surgeon. Then my first year of med school, we got our first cadavers, and there was so much data inside. You can be sure a patient will lie about how much they drink or how much they smoke, but with a cadaver, all the information is there." She lights another cigarette and sighs. "It's like walking through a stranger's house and touching all their things."